Introduction

Since antiquity a clear association has been made in western culture between literary and artistic activity and urban society. Artistic and literary institutions have been a defining element of urban life and essential to the rhetoric of urban civilization. In the modern era the concept of the "creative city" has been coined that assumes a direct correlation between urbanity and creative development.1 Thus Jane Jacobs (1916–2006) famously argued in The Economy of Cities (1969) that the dense concentration of diverse populations in the urban environment created the precondition for innovation and economic development.2 Her argument has provoked scepticism from a number of quarters: cities are not and should not be seen as the only environments that produce, foster and encourage creativity and neither should we simply assume that, if certain criteria of size and heterogeneity are met, a burst of creativity is bound to happen. However, while this article cannot claim to provide an explanation of the complex relationship between creativity and (urban) economic development, by looking at creative metropolises from 1450 until 1930 we do intend to tackle those specific urban centres that succeeded in becoming literary and artistic centres of global significance from the early modern period onwards.

Whilst all urban societies can be said to engage in cultural production at some level there have always been certain cities that have been particularly renowned as centres of such activity and which we might describe as literary and artistic metropolises. For such cities the production and consumption of art (whether paintings, sculpture, architecture or music) and literature becomes a key part of the urban economy, and also part of the city’s identity and reputation. The relationship between a particular city and a specific cultural form is often so close as to be synonymous: for example, 17th-century Rome and the baroque or 19th-century Paris and the Beaux Arts movement. By literary or artistic metropolises, then, we understand cities which were centres for production, consumption and dissemination of the arts and literature on a global scale, which for the period 1450–1930s primarily meant Europe and its colonies.3 These literary and artistic metropolises emerged not least because they were also nodal points in other networks of communication and exchange, and it was the very fertility of new ideas, new products, and technological innovation, as well as the resources of wealth and patronage in a flourishing urban economy, that enabled these cities to assume a role of cultural leadership. Thus we put special emphasis on the networks that link the cities to each other and, consequently, on those cities that succeeded in spreading their artistic production through the existing networks on the transcontinental scale. At different points in European history a variety of cities have acquired reputations as literary or artistic metropolises: some, such as Rome, Paris or London, display an almost unbroken line of artistic and literary dominance across several centuries; others, such as New York arrived late on the scene; and some such as Dresden, or early 20th-century and interwar Moscow, flowered for briefer periods, but continue to be shaped by and benefit from the legacy of earlier cultural efflorescence, even if their literary and artistic influence diminished over time. Many other cities deserve our interest, too, and will be treated in the larger comparative context.

Artistic and literary production are not inherently urban processes in themselves but they have always flourished in an urban context and in considering how and why certain cities have emerged as literary and artistic metropolises, it is worth identifying some of the reasons that enable such cultural flowering to take place. In the first instance the urban economy has always generated much of the surplus wealth essential for the purchase or commissioning of art and literature.4 The availability of capital and surplus wealth has also been essential for the technological innovations in cultural production, whether it be the investment needed for the printing press which underpinned the literary metropolis of the 16th century or the construction of theatres and opera houses in the 19th century. Due to their density of population, cities have also constituted a higher concentration of demand which encourages the production of high valued goods. Similarly, the urban economy offers a concentration of specialized skills, the product of higher levels of education, training and competition found in cities, whether provided through the guilds of early modern Europe or the art academies or the conservatoires of the modern period. The success of artistic and literary metropolises has also drawn upon the trading networks of the urban economy: these offer the means for sale and distribution of artistic productions and the dissemination of cultural influence. But equally importantly these networks have also been the channels through which new goods, new ideas and new talent (in the form of migrant labour) arrived facilitating the innovation that has sustained cultural dominance.

In many centres, as artistic production became institutionalised, it was used to justify urban improvement, to promote local patriotism and to enhance prestige. Well-established artistic or literary metropolises have exploited their status to attract more innovation, more artists and more investment in the arts; centres which lacked a comparable cultural dynamic often aspired to create one, either through monarchical or state involvement or through the intervention of municipal authorities. Thus the influence of artistic and literary metropolises spreads not only through the exchange of goods and ideas, but also through emulation and urban rivalry. In some cases the "cultural capital" of being a literary and artistic metropolis has also helped to counteract the consequences of commercial or manufacturing decline. Finally, it is important to remember the importance of urban space as well as the urban economy in stimulating artistic and literary production: without the proximity of urban living there would not be the possibility for the cross fertilisation of ideas, skills and information that Deborah Harkness has identified as an "urban sensibility".5 Without the spaces of coffee houses or art galleries, there would not be the opportunities for the exchange of ideas, the development of the language, of taste and criticism, or for the emergence of a public that consumes the cultural products.

This essay begins with the cities that dominated the flowering of urban culture in the late 15th century commonly termed the renaissance. This is not the place to discuss the origins of the renaissance or the different interpretations, but in this context it is important to emphasise that it was, overwhelmingly, an urban phenomenon, concentrated in the urban hotspots of Europe –northern and central Italy and in the Low Countries.

The Renaissance City in Italy and the Low Countries

Traditional histories of the renaissance often concentrate on the city republic of Florence, where Giotto di Bondone (ca. 1266–1337)[

During the 14th and 15th centuries the prosperity consequent upon international trade had encouraged generous patronage of the arts as guilds, the chief political institutions of the city, vied with each other to commission artworks in churches, hospitals and other religious and civic buildings and spaces. Similarly surplus wealth stimulated the demand for luxury goods and other small works of art. Art offered the means to communicate power and prestige, commercial success and political influence. The decoration of the Duomo

By the 15th century the city had fallen increasingly under the dominance of a single family, the Medici, although ostensibly still a republic, and correspondingly the pattern of patronage shifted away from corporate bodies to private families, led by the Medici and their supporters. They modelled themselves on the patrician elite of ancient Rome, private individuals collecting art as an aesthetic experience for their own enjoyment, as well as making a statement of wealth, or civic pride or religious piety. Lorenzo de’ Medici (1449–1492)[

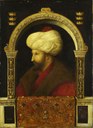

Florence was one of a network of prosperous Italian cities through northern and central Italy, and in the Low Countries cities such as Bruges, Antwerp and Brussels similarly came to prominence amidst a more widespread boom in urban development based upon textiles and overseas trade. In these cities we find the same concentration of skill and sophisticated training structures dominated by guilds and the same generation of surplus wealth that encouraged the commission of art works for reasons of piety, civic pride or conspicuous consumption. Unlike the Italian cities, those of the Low Countries concentrated artistic production on smaller artworks on wooden panels that were easily exported along existing trade routes and the Pand market in Antwerp, for example, was the most important public art market in Europe.11 Venice was different again: as a bridge between east and west, it highlights the importance of overseas connections in sustaining an artistic metropolis.12 The constant traffic of goods and people from around the world facilitated the introduction of new goods and techniques, evident in the eclecticism of the city’s unique architectural heritage, or the tangible influence of the Ottoman Empire upon Gentile Bellini’s (ca. 1429–1507) portrait of Mehmet II (1432–1481)[

Rome: Art and Religion and the Rise of the Baroque

By the 16th century Florence, Bruges and latterly Antwerp were in economic decline as their trading networks were taken over by other cities. However, they did not lose their influence as artistic or literary metropolises altogether, and past reputation continued to shape the cities’ image through subsequent centuries. The dynamism of the creative hubs, however, moved to Rome and, by the late 16th century, to Amsterdam respectively. Rome, unlike Florence, never had a significant commercial or manufacturing base, but it did command, through the Roman Catholic Church, enormous resources of patronage and wealth. Ever since the return of the papacy to Rome in 1420, following the Avignon exile, the popes had been concerned to enhance their authority through the patronage of the arts, in many cases using Florentine trained artists, including most notably Raphael (1483–1520) and Michelangelo (1475–1564). In the 16th century this took on new urgency in the Counter-Reformation, as the arts were co-opted into the battle against heresy and into the assertion of the Church’s spiritual and secular authority. Rome’s political, religious and cultural importance had never been higher and it became the centre of artistic innovation and the creation of a new art form – the baroque – the influence of which through art, architecture, music and sculpture, is still visible in cities across the world.14

Whereas Florence or Antwerp benefited from the networks of international trade for the dissemination of style, goods and craftsmen, in Rome the networks were those of the Catholic Church itself, the most administratively advanced and sophisticated transnational organization of the early modern period. It was also the destination for thousands of religious pilgrims every year who were witnesses to the extraordinary displays of artistic achievement. The church’s wealth created multiple opportunities for artists and craftsmen and the city soon developed the institutions to train them, with the establishment of the Accademia di San Luca (1577). Rome’s importance as a training centre for artists across Europe is evident in the numbers of foreign artists who came to study in the city and the foundation of foreign academies such as the French Académie de France (1661). As a consequence the city’s reputation as a centre of artistic excellence became an increasingly important aspect of its own self-promotion and one which was actively encouraged by the Papacy, whose collections in the Vatican Museums were amongst the first to be opened to visitors. Art became part of the city’s identity and patrimony, celebrated in guidebooks bought by pilgrims and cultural tourists from the 17th century onwards.15 Rome was not only a centre for the patronage and execution of innovative art, but it was also, increasingly, a centre for its retail and distribution. During the 17th century shops specializing in paintings and antiquities sprang up, and middle men or dealers specializing in sale or commissioning of painters began to emerge. Rome also saw the development of an anonymous art market, with dealers such as Pellegrino Peri (1624–1699) who employed migrant foreign artists to work for him producing paintings to order which would be sold to collectors.16

The dynamic energy that had driven the innovations of the baroque era dissipated from the late 17th century, but nonetheless Rome’s primacy as a centre for artistic production continued through the 18th and 19th centuries.17 This was partly due to the concentration of artworks which defined the canon of European taste, and partly due to the institutions and infrastructure that had developed (from art academies to art markets) that drew artists and collectors to Rome. A sojourn in Rome was an asset in the career of any aspirant artist or architect and it was Rome’s reputation as an artistic metropolis, combined with its legacy of classical antiquity, that sustained and continues to sustain much of its economic activity.18

Cities of Print: From Venice to Antwerp and Amsterdam

By the 16th century, the widespread establishment of the printing press and the consequent development of print culture makes it possible to consider cities as literary metropolises: that is centres of literary production and consumption, in a way that is not possible even for centre of renaissance humanism such as Florence. Venice, for example, like other renaissance cities was also home to a flourishing tradition of humanist scholarship, but was unique in the rapidity with which the printing press became established. Venice’s mercantile wealth meant there was ready availability of capital to invest in the new printing presses and by 1500 there were 150 Venetian presses churning out over 4,000 editions of different books. This output represented between an eighth and a sevenths of the total production of Europe at the time. As the focal point of print production, Venice was also central in the exchange of ideas and informal academies grew up around the publishers such as Aldo Manutio (ca. 1450–1515).19 But Venice was also one of the earliest centres for the printing of music, reflecting both the vitality of the musical traditions in the city itself, and also an international reputation for specialist skill in printing that drew composers and musicians from across Europe.20

Venice’s mantle as the dominant city for print culture was challenged firstly by Antwerp and increasingly by Amsterdam during the 17th century. For both cities, like Venice, the wealth generated through international trade facilitated access to capital at low rates of interest which in turn encouraged entrepreneurial investment in the new technology of printing presses. In the mid-16th century Christophe Plantin’s (ca. 1520–1589) "printing plant" at the Golden Compass in Antwerp comprised 22 presses that employed 160 workmen utilising multiple fonts for printing in different languages for Antwerp’s European market.21 In the 17th century, as Amsterdam took over the trading networks of Antwerp, it also found a ready market for printed books which could be exported in bulk, be they English Bibles, Hebrew texts for Eastern Europe, or forbidden texts for neighbouring France.22 Amsterdam, as a commercial city with a republican structure of governance, avoided the censorship of politics and religion that stifled debate elsewhere in Europe. Religious and political refugees flocked to Amsterdam and the Low Countries, bringing their traditions of scholarship and the city’s traditions and networks of print culture ensured the wider dissemination of their ideas.23 Most importantly Amsterdam became a centre of news and newspaper production, effectively creating a format of communication that has become ubiquitous across the world. Amsterdam was an intellectual as well as a commercial entrepôt city.24

New Patrons and Consumers: From Aristocrats to the Bourgeoisie

For all that the reputation of Rome and Florence as centres of literary and artistic excellence lingered on throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, sustained by the cultural institution of the Grand Tour, this was nonetheless a reputation that was largely historic and rested on former glories rather than current achievement. There was a strong sense amongst contemporaries that the impetus of artistic creativity had shifted northwards and westwards, to centres such as Paris and London, and to a lesser extent Berlin, Vienna or Dresden. In the latter cities the presence of the resident court and nobility provided the patronage and the cachet that attracted both the artists and other consumers. In capital cities and the Residenzstädte the arts were harnessed to the project of enlightened absolutism and as a means of glorifying and legitimating the authority of the ruling prince.25 Royal or aristocratic patronage remained essential for every art form during the 18th century, whether in the form of subscription, subsidy or sinecures.26 Art, music and literature did not, of course, come cheap; however, what is evident in the 18th century is that the market for such cultural products began to expand in response to the increasing significance of the urban bourgeoisie as consumers of and participants in artistic and literary production. From this sprang other developments such as the emergence of a sophisticated art market in cities; the development of a culture of public viewing, public taste, and discussion and the commodification and commercialisation of the arts and of leisure more widely defined. Across Europe it became widely accepted that the cultivation of the arts was an index of the degree of civilization to which that city or state had attained. These are themes which the following paragraphs will explore in more detail.

Marketing Art and Defining Taste

In London it is clear that the middling consumers of the rapidly growing city played a vital role in the development of the city’s art market which rapidly emerged in the late 17th century effectively taking over from Amsterdam, as it had in the area of international trade. In 17th century Amsterdam, the wealth of the prosperous middle classes had generated a lively demand for smaller artworks, suitable for the home, depicting scenes familiar to a middling lifestyle such as the new genre of townscapes. These were produced by hundreds of artists and sold in their thousands at auctions to be purchased by a socially diverse community of merchants, craftsmen, dealers and collectors for largely private display.27 Like the Dutch, Londoners were apparently consumers with homes full of pictures, if not great artworks. By 1700 the city supported a sizeable community of artists, catering to the needs of a rapidly growing population with the discretionary income to purchase works of art to ornament their homes.28 At the other end of the market, well-heeled patrons returning from the Grand Tour imported paintings (and artists) to London on an ever increasing scale, or purchased them at auction.29 Regular auctions in London’s coffee houses soon established the city as one of the leading centres for the sale of paintings in Europe. Those who could not afford the price of oil paintings could purchase engraved prints in a rapidly diversifying market. The combination of highly skilled craftsmen, many of whom were Huguenots who had fled to London from persecution in France, and the buoyant demand from London’s middle classes, encouraged constant innovation and competition amongst the engravers. William Hogarth's (1697–1764) Modern Moral Subjects – in which the city of London itself played a prominent part as the backdrop to his satire and social commentary – embody both the innovation of technique and the appeal to the values and morals of a decidedly bourgeois market characteristic of the time.30 London also became a centre for the display of art and the discussion of taste: venues soon became established, emanating initially from the multi-functional spaces of coffeehouses and developing into the sale rooms of auction houses, or public spaces such as the Foundling Hospital, where Hogarth and Joseph Highmore (1692–1780) displayed their work, or the annual exhibitions of the Royal Academy in the latter part of the century.31 In Paris, historians have similarly identified a shift away from exclusively private and aristocratic patronage of art towards a more public audience with the establishment of the Salon in 1737. This was an exhibition of paintings held in the Louvre by the Academy of Painting and Sculpture and, unusually for the time, open to the public. By 1781 it was attracting as many as 30,000 visitors and up to 10,000 catalogues were being printed.32 Whilst there were many who complained at the invasion of the realm of "taste" by the "vulgar" there was no turning back. In Paris and London taste and connoisseurship became topics for public debate through the medium of newspapers and periodicals or in coffee houses and salons, where aristocratic influence was also having to make room for an increasingly influential bourgeois presence.33

Print Culture and Urban Space

Print culture, then, was the bedrock on which the public audience for art was constructed and growth of the art world was inseparable from its literary environment. Throughout Europe falling prices and increased production meant that print culture was becoming a more affordable and accessible feature of urban life. For reasons of state censorship, as well as issues of infrastructure, markets and logistics, newspaper and book production were heavily weighted towards the capital cities such as Vienna, Paris and London. New formats (the periodical, the review) and new genres, such as the novel and the essay, generated ever-widening opportunities for the profession of letters while the venues of coffee houses, salons, subscription libraries and booksellers’ premises facilitated literary discussion and debate.34 Landmark publishing ventures such as the 28-volume Encyclopédie ou dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers

Music and Transnational Exchanges

The growth of a public music and theatre followed a similar pattern to that of art and literature, as the patronage of a narrow court elite gave way to a more commercial and entrepreneurial system in which bourgeois taste and fashion played an increasingly important role. Teresa Cornelys (1723–1797), the Venetian born opera singer, was the most famous exemplar of the new-style of musical impresario in London.41 Capital cities such as London and Paris flourished as cultural centres precisely because of the opportunities they offered for artistic entrepreneurial success and because they had acquired the reputation as centres of fashion, taste and innovation.42 As the seat of government and the centres of elite society, as well as being commercial hubs, these cities exercised a powerful gravitational pull over the nation’s cultural life. Theatres, the principal entertainment for fashionable society, proliferated: in Paris theatre capacity stood at a total of 13,000 (for a population of ca. 650,000) on the eve of the Revolution; in London state regulation restricted their number to three, the largest of which at Covent Garden could seat over 3,600 by the end of the century.43 The number and quality of theatres became a standard index by which any city’s claim to fashionable status could be judged. In Great Britain opera was a far more expensive form of entertainment and exclusively metropolitan, but unusually for the time, was run as a commercial business, reliant upon ticket sales and subscription for its survival, rather than princely patronage.44 But, for those who were excluded by prohibitive prices, musical performances were available on a much more affordable basis through commercial pleasure gardens such as Vauxhall

Elsewhere in Europe for Italian cities such as Naples, Venice or Rome or German cities such as Dresden, theatre and music arguably assumed an even more prominent role in the absence of significant commercial or manufacturing developments. Here the provision of musical and theatrical entertainment played a central part in the cities’ economies, dependent as they were on catering to the demands of resident nobility and attracting the custom of wealthy travellers making the tour of Europe. Private patronage, however – from the monarchy or nobility – provided an essential subsidy.46 Venice, the birthplace of opera, famously boasted seven theatres, more than any other city in Europe, and in Naples the magnificent Teatro San Carlo, under royal patronage, was a tourist destination in its own right.47 Musicians trained in Naples and Venice were in high demand across Europe: London played host to the castrato Farinelli (Carlo Broschi, 1705–1782) in 1734 and in a single decade he performed in Rome, Vienna, Naples, Milan, Bologna, Munich, Venice, Vienna (again), London, Paris and finally Madrid.48 Metastasio (Pietro Trapasisi, 1698–1782), whose libretti for opera seria were translated into all the major European languages of his day, or Carlo Goldoni (1707–1793), the Venetian librettist who helped to transform opera buffa into an art form, similarly moved from one 18th-century metropolis of music to another: from Rome to Vienna, from Venice to Paris.49 Farinelli’s career illustrates the networks between centres of music education where the future singers were trained, centres of power such as royal and aristocratic courts and, if not identical with the latter, centres of large public audiences. The European success of Italian castrati, followed by that of classical opera singers, composers, virtuosi and the travelling ensembles performing music to increasingly modern and urban audiences, would have been unthinkable without the existence of this network. As the courts and the aristocracy gradually moved into permanent urban residence, training and learning music increasingly became an urban affair, too (seen in the 19th-century foundation of conservatoires). While the role of Italian training centres would remain pivotal for the emergence of music stars such as castrati and, later, opera singers, larger European capital cities such as Paris, London or Vienna were to become decisive for their eventual success. It is not difficult to see why this was the case: not only did music superstars require large audiences that only the largest cities could offer, but they also increasingly relied on the role of the press in the dissemination of this success and to generate a sense of expectation and anticipation amongst the audiences of the cities they visited.50 This eventually led to select music metropolises – Paris, Milan, Dresden, Vienna – dictating music taste and eventual success for every aspiring talent during the 18th and the 19th centuries.

The Rise of Paris

Few cities have been the subject of more attention in literature, the arts and scholarship than 19th-century Paris.51 Following Walter Benjamin’s (1892–1940) Arcades Project, which equated Paris with the essence of the century,52 many scholars interpreted the city variously as an embodiment of revolution, modernity, the spectacle of imperial and bourgeois representation and the cultural and artistic capital of the world. This extraordinary attention and the influence Paris had on other artistic and literary metropolises are unprecedented in modern history.53 The literary and artistic reputation of the most influential 19th-century Parisians – Honoré de Balzac (1799–1850), Charles Baudelaire (1821–1867), Émile Zola (1840–1902) and the impressionists, to name but a few – span far beyond the city borders of the French metropolis. Each dedicated to the recording of the metropolis in their own way, they drew from the new poetics of urban modernity. Baudelaire’s Les Fleurs du Mal is, in many respects, an opus dedicated to the modernisation of the French capital during the Second Empire and the entire Haussmannisation project, in which the poet saw as many signs of change as of decay. One of the most perceptive writers of the modern city and the inventor of the concept of a flâneur (later glorified by Benjamin), he was acutely interested and extremely influential in other arts, especially fine arts and music. While his literary success was due to the novelty and provocative character of his themes as much as his literary genius and skill, the fact that his work became an unprecedented success not only in Paris but also across the continent is largely due to his analysis of the artistic life of Paris of his time and the web of artistic networks within and beyond the Parisian capital to which he belonged.54

What Baudelaire’s example illustrates is the centrality of Paris as the art metropolis of Europe overshadowing all other larger cities, in which a fundamental transformation was taking place along with a high concentration of professional academic art institutions, fierce competition in art, music and theatre, the booming of salon culture, bohemian existence, and the emergence of new artistic movements. The new modern city and its distinct phenomena such as extreme density of population, social inequality, the luxury life of the upper class, and flânerie then became the subject of art itself.55 French Romantic art, of which Eugène Delacroix’s (1798–1863) Liberty Leading the People (1830)

In the 19th century, Paris gradually replaced other cities in Europe as a main tourist destination and as a place of artistic education. While many still embarked upon a Grand Tour to Italy, a trip to and residence in the artistic quarters of Paris became pivotal for the success of so many careers across the continent that it would be impossible to mention even the most important names in this short article. The birth and development of Jugendstil in Berlin and Munich and Sezession in Vienna – or, for this matter, similar developments in other cities of Eastern and Central Europe, such as, for example, the emergence of the St. Petersburg journal Mir iskusstva (the world of art) – would have been impossible without intense contact with the artistic centres of Paris including but not limited to those working within the stylistic constraints of art nouveau. The Viennese Sezession movement, a large and heterogeneous group of artists loosely united under the ambition of abandoning the academic art of the main official artistic institution, the Künstlerhaus, which was dominated by historicism, in order to create art without historic precedent and based on entirely new aesthetics, was largely responsible for introducing the local public to French impressionism. At the same time, Sezession’s offspring, Josef Hoffmann’s (1870–1956) and Koloman Moser’s (1868–1918) Wiener Werkstätte, indicate much stronger links with the British Arts and Crafts movement.59 As in early modern Florence and Amsterdam, fin-de-siècle art across the continent would be unthinkable without a large group of patrons, connoisseurs and supporters who provided the movement with financial support, as well as the eager and attentive public. In a parallel development, writers in other capitals targeted the modern city in their work. Charles Dickens’ (1812–1870) London, Arthur Schnitzler’s (1862–1931) Vienna, Franz Kafka’s (1883–1924) Prague, Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s (1821–1881) St. Petersburg are only the most striking examples of writers who, in contact with and in response to each other, as well as the work of Baudelaire, Balzac and Zola, created their own visions of the modern literary metropolis.60

Though the choice of the city as the subject of art in Paris and elsewhere has a long history, perhaps the first images that come to mind when thinking of art in a modern metropolis are the works of the impressionists. A whole large range of paintings starting probably with Édouard Manet’s (1832–1883) A Bar at the Folies Bergères (Un bar aux Folies-Bergères, 1881–1882)

Rainy Weather (Rue de Paris un jour de pluie, 1877) and The Europe Bridge (Pont de l’Europe, 1876)

Fin-de-siècle Cultural Transfers in Architecture, Theatre and Music

The way the new, innovative trends such as impressionism, caricature, music hall, operetta, cabaret and others interacted in everyday life with the popular culture has recently received much scholarly attention.62 All around the continent new artistic and literary circles emerged that met, debated and often even lived in particular coffee houses – another urban element so characteristic of a modern literary and artistic metropolis. In a parallel development affecting musical life in European metropolises of the time, a gradual diversification of both the genres and the public can be observed there. While opera houses continued to serve as venues of self-representation for the upper classes, despite repeated attempts to reform the genre, its architecture and the habits of the public across the continent,63 music halls, operetta and comic theatres emerged as fundamentally middle-class venues with their own distinct repertoire and public. As Haussmannisation swept through the continent and cities were reshaped to fit the new ideal of urban planning and historicist representation, the location of these venues in the city often began to signify their symbolic importance in the eyes of the ruling elite: opera houses were built on the most representative boulevards and squares, while other venues were located in less central and less prestigious quarters. Ironically, the further away the location from the prestigious avenues, the more local and urban it tends to become.64 The Palais Garnier and the Dresden Opera House, constructed by the leading architects Charles Garnier (1825–1898) and Gottfried Semper (1803–1879) respectively, provided the model for many opera houses across Europe: that is, a building in which the three functionally separate spaces – the foyer, the auditorium and the stage – were visibly distinguished from the outside as much as from the inside. This model was applied throughout the continent to music theatres as diverse as Odessa Opera Theatre (1887), Viennese Burgtheater (1888) and Teatro Massimo in Palermo (1897). In a parallel development, Richard Wagner’s (1813–1883) innovations in the realm of stage design, together with calls for further restructuring of the boxes in the auditorium to accommodate the increasing presence of the middle classes, produced an entirely new public space in which previously impossible social encounters were possible and in which the public behaved differently from the unruly and laissez faire audiences for which opera houses had been notorious before.65 The fact that this theatre building model could be mass produced by the turn of the century and that companies such as Fellner and Helmer in Central Europe could construct over 200 public buildings, mostly theatres, in roughly thirty years, is illustrative of the intensity of the architectural, artistic and musical networks in turn-of-the-century Europe.66 It was in these theatres that the famous music stars of the time – from composers such as Franz Liszt (1811–1886) to singers such as Enrico Caruso (1873–1921) and performers such as Sarah Bernhardt (1844–1923) – performed when they started their European tours.67 This period also witnessed the emergence of operatic musical ensembles, such as Angelo Neumann’s (1838–1910) Richard Wagner Ensemble, whose tours across the continent resulted in, according to one estimate, 135 performances of The Ring and 50 Wagner concerts in 1882–1883 alone.68

All these developments led to the demise of Paris as the paramount capital of 19th-century Europe. At the fin de siècle, an increasingly large number of cities joined the rank of the old artistic and literary metropolises and claimed to stand on a par with them in regards metropolitan culture. This can be largely attributed to two parallel but related phenomena: the birth of a truly cosmopolitan urban culture of modernism and the development of modern nationalism. Routinely cities of secondary importance in the empire developed into centres of national literature, culture and art – Barcelona, Rome after the Italian unification, Budapest after the Austrian-Hungarian compromise 1867, fin-de-siècle Prague, Cracow, Lemberg, Kiev, Odessa, Moscow and the capitals of the Balkan states (Athens, Belgrade, Sofia) that emerged as the Ottoman Empire gradually lost its European territories are cases in point. At the same time, modern national celebrations making use of art in the same way that imperial celebrations had done so in the past, became increasingly dominant in urban space, and old urban ceremonials were transformed to fit the national agenda, too.69 Public discussions took place in many urban cultural venues on whether or not art should remain international or alternatively serve national goals: literature, opera and drama were especially under pressure to address nationally relevant topics, whereas operetta, vaudeville and comic theatre became increasingly a truly urban phenomenon.70 While the literature on the development of national capitals that competed with the imperial centres and fostered a specifically national culture is huge, the number of works on imperial representation and cosmopolitan artistic and literary life in the same centres is constantly growing, too. Particularly interesting is the recent research on 19th-century Ottoman cities, from the imperial metropolis Istanbul to regional capitals such as Salonika, Aleppo, Beirut and Cairo, which demonstrates vividly what has already been established for other "peripheral" regions such as East-Central Europe: neither did the imperial culture decay as a consequence of modernisation processes, nor was the development of regional metropolises exclusively due to cultural transfers from Western Europe or the emergence of modern nationalism.71

20th Century Avant-Garde Urban Circles

The 20th century saw the birth of modernism and its futurist and urban poetics. Smaller avant-garde circles centred on specific coffee houses or other urban venues emerged in every larger city and yet remained in constant touch with other, similar centres in other cities. One example of this new cultural phenomenon is the emergence of cubism in Paris. The so-called Montparnasse group that included, among others, Albert Gleizes (1881–1953), Jean Metzinger (1883–1956), Henri Le Fauconnier (1881–ca. 1945) and Robert Delaunay (1885–1941), Fernand Léger (1881–1955) and Marie Laurencin (1883–1956) – artists whose name would become synonymous with cubism – met and organised their activities in a number of Montparnasse cafés as much as in art studios. They eventually took over the hanging committee of the Salon des Indépendants, ensuring that cubist works would be shown together in one room at the exhibition in 1911. This eventually produced a scandal of massive scale and ensured that cubism would soon become one of the dominant artistic styles in Europe.72 Avant-garde and the features associated with it – the non-conformist lifestyle, opposition to mainstream cultural values and to high culture itself – is a fundamentally urban phenomenon that could emerge and flourish only in larger cities. There is no place in this short article to enumerate all the diverse examples of artistic and literary groups that emerged in different European cities in the early 20th century and whose influence sometimes remains with us until today. Dadaism in Zurich and Berlin, Cubism, Fauvism and Surrealism in Paris, symbolism in Paris, Brussels and St. Petersburg, diverse branches of expressionism in Dresden, Berlin and Munich, Futurism in Rome, Moscow, St. Petersburg and Kiev, constructivism in Moscow and other Russian centres, Bauhaus in Weimar and Berlin, De Stijl in Amsterdam and individuals such as Oskar Kokoschka (1886–1980) and Egon Schiele (1890–1918) in Vienna and Edvard Munch (1863–1944) in Paris, Berlin and Christiania (Oslo) are only the best known examples. Many of these movements and artists poetised the new modern metropolis in many diverse ways, and some also voiced fundamental social criticism of contemporary society. As with the art colony of 19th-century Paris, these essentially urban avant-garde movements would not have functioned in the way they did and would not have dominated public space in European cities in the early 20th century and during the interwar period had they not been linked to each other through personal, educational and career networks across the continent.73 Modernist education centres soon emerged in Paris, Vienna, Munich, Berlin and St. Petersburg, with a regular circulation of artists between them. New modernist art periodicals such as "Der Sturm" in Berlin propagated avant-garde aesthetics and literary and artistic production further. This epoch also witnessed the birth of musical modernism: the works of Richard Strauss (1864–1949) and Béla Bartók (1881–1945) and Sergej Diagilev’s (1872–1929) Ballets Russes are the most illustrative examples. At the same time, urban photography, journalism and film developed: Fritz Lang’s (1890–1976) Metropolis and Dziga Vertov’s (1896–1954) Man with a Movie Camera are the most striking examples that serve as an avant-garde tribute to the modern city in this new medium.74

Among the many interesting (but also distressing) phenomena associated with what became known as the Generation of 1914, Génération au Feu or Lost Generation were the consequences for post-war Paris. The city had always been a profoundly international metropolis, and among many others, some of the most important writers of American modernism (F. Scott Fitzgerald (1896–1940), Henry James (1843–1916), T.S. Eliot (1888–1965), Ernest Hemingway (1899–1961)) spent a decade or more there and found their spiritual home under the auspices of Gertrude Stein (1874–1946). With all their "gods dead, all wars fought, all faith shaken"75 these artists contributed to the flourishing of Paris as an artistic and literary metropolis and, at the same time, to the emergence of American modernism. Parallel developments characterise the urban life of interwar Berlin and other cities. Cabaret and Jazz emerged as a central urban phenomena during the interwar period, too.76

Conclusion

The 20th century is characterised by an unprecedented proliferation of modes of artistic expression and representation, assisted by the rapid technological developments of radio, television and the electronic age. The subject requires another essay in its own right. What this essay has illustrated is how and why certain urban centres have assumed dominant roles in the process of artistic and literary production, dissemination and exchange, and how, in many cases, a pattern of path dependency sets in, ensuring that the reputation is perpetuated and built upon in subsequent generations. Although we now live in a world in which more than fifty percent of the population is urban and increasingly connected, through both physical and virtual networks, certain cities – Paris, Rome, London or Vienna – continue to command a reputation for cultural creativity that derives much of its legitimacy from the historical antecedents that this essay has discussed.